“Today we’re going to study the food pyramid for healthy living!” the High School Social Science teacher Mark told his class. Mark was excited about launching a healthy food project that would enable kids to analyze their diets. He was well-prepared and had collected a number of teaching resources from government agencies, NGO’s and food-companies concerned with youth obesity and increasing health costs. One of his students called out: ”Food pyramids?” Boring! Why can’t we go to McDonalds?” This idea got the whole class excited, but frustrated Mark. After all, he had thought of something new that was hands-on and seemed very relevant. Later that evening Mark asked himself how he could motivate his students and engage them in an exciting learning process that would teach them something about health issues. He got an idea.

The next day Mark said to his class: “Today we’re going to McDonalds!” The whole class cheered. They couldn’t believe it. Their teacher was actually going to take the whole class to the McDonalds near the mall across the street. “But…, there’s one condition. We will only buy one happy meal for the whole class”. This got the students a little less excited, but they went anyway, just to get out of school. The class bought one cheeseburger happy meal and took it back to the classroom. Mark told the class that “unfortunately we are not going to eat the happy meal, we are going to carefully study it instead”. He wrote down two questions on the blackboard:

What is in it?

Where did it come from?

They first dissected the meal: a plain bread bun, a slice of melted cheese, a grilled beef burger, salt, mustard, ketchup, pickles, French fries, diet cola, and, finally, a nice toy.

Then Mark divided the class in six groups of four students. One group got the bread bun, another group the salted French fries, another group the diet soda, another group got the burger, another group the accessories; ketchup, mustard and pickles and the last group got the plastic bagged happy meal toy.

“You have the remaining social science hours of the week to answer the two questions. Next week I want a short presentation with your findings from each of the groups. You can use the internet, the school library, the telephone in my office, and, if you need to ask questions across the street at the restaurant you can do so with my permission.”

All the groups went to work and the more they found out, the more interested they got. The group investigating the french fries found out that fast food chains need enormous volumes of potatoes and demand a certain type of potato that guarantees a consistent quality. As a result potato farmers around the world have reduced the number of potato varieties greatly. This has led to a loss of crop-biodiversity, making the remaining crops more vulnerable to pests and leading to an increase of pesticide use. A common response to this vulnerability is use genetically modified crops that are resistant to these pests. However the students also found out that McDonalds, pressured by concerned consumers, decided not to use Monsanto’s GM new leaf potato. The group’s investigation led to an interesting discussion about the pro’s and con’s of GM-foods. Most students were not aware that they were already consuming GM-foods. In fact the group studying the diet Cola found out that the sweeteners contained GM corn. When presenting their finding students used a provocative quote from the internet to start a classroom-wide discussion:

Giant agribusiness, chemical and restaurant companies like Cargill, Monsanto and McDonalds dominate the world’s food chain, building a global dependence on unhealthy and genetically dangerous products. These companies are racing to secure patents on every plant and living organism and their intensive advertising seeks to persuade the world’s consumers to eat more and more sweets, snacks, burgers, and soft drinks.

Meanwhile the group investigating the happy meal toy learnt some things they didn’t expect to learn either. The discovered that the toys served cross-marketing purposes. Meaning that they bring parents and their children to the restaurant but they also promote things like Disney movies. Most of the toys were made of plastic and not used by the children for a very long time. They went back to the McDonalds and studied how and for how long kids played with the toy and asked parents to estimate for how long the toy would remain in use. They estimated that the effective play time would be less than 10 minutes. Perhaps the most interesting finding they got by using the Internet. They found many sites – mostly activist sites – that suggested that the happy meal toys were made in China. They came upon an article that stated that “.. a happy meal toy manufacturer, China-based City Toys Limited, employed children as young as 13 to assemble the “Happy Meal” toys.” These young teenagers were reportedly forced to work 16 hour days, seven days a week, and lived in crowded, on-site dormitories for a salary of less than 3 dollars a day. As a result of these revelations made in the Summer of 2000, McDonalds quickly responded by denying to have any knowledge about these conditions. The company distanced itself from City Toys Limited and moved its operations elsewhere. Since McDonalds was, at the time, not required to disclose information about its overseas contractors, it was difficult for the students to trace where they moved the operations and what the working conditions are at the new facilities. When this group presented their results to the class the were discussions about child-labour, children’s rights, ethics of moving jobs to countries with different standards and laws, but also about the consequences of McDonalds using a ‘cut-and-run’ strategy for the children in China working for City Toys, whose income might have been crucial for their families. The teacher also raised the issue of the reliability of the information of provided on the internet. Who put the information there? With what purpose? Is it based on fact?

The other groups too, found interesting information and point of discussion related to a happy meal (varying from beef imports, hormones in meat, clear cutting of rainforest to the sweeteners used in Diet-coke). One group was interested in figuring out ‘how many miles a happy meal has travelled to get to the local McDonalds? They didn’t get a chance to figure it out but they guessed tens of thousand of miles. The whole excersise was transformative in that they view of fast food in general and of a happy meal had changed. Mark’s concern was that, even though the students learnt a lot about food-related sustainability issues (health, environment, equity, economics), gathering information, presenting information, critical thinking, debating, etc., the project may have resulted in a rather bleak picture of something they really enjoyed: eating a nice juicy cheeseburger at McDonalds. He wanted the students to think about viable alternatives. So he asked the students a third question:

Can you design a happy meal that makes everybody happy?

The same groups started thinking about alternative buns, cheese, beef, mustard, pickles, soda, and even an alternative toy. This took another week of investigations but in the end they designed a happy meal that was more organic, healthier, socially-responsible and used up less energy. They cooked the happy meal themselves in the school kitchen for all junior high students and did a taste survey which demonstrated that the meal was a least as tasty as a McDonalds happy meal. There was one problem: the new happy meal was far more expensive that the McDonald’s version. This raised another issue in the classroom: are we willing and/or able to pay more for meals that are healthier, more equitable, have less environmental impact? Some argued that consumers should demand this kind of food so that big corporations will change their own policies and practices, making alternative foods more affordable as demand increases.

“When McDonalds, Pringles, and the other major potato buyers decided not to sell Monsanto’s GM New Leaf potato, for example, it was soon taken off the market. McDonalds and others doomed Monsanto’s potato because they wanted to satisfy consumer demands. We have that power.” “In the U.S., Whole Foods Market, Wild Oats, and Trader Joe’s announced that GMOs would be removed from their store brands. Gerber baby foods, as well as scores of health food products, have similarly changed their ingredients.”

“When a store or brand removes GM ingredients, it has a ripple effect through the industry. After a supermarket chain commits to eliminate GMO’s, they usually send out a letter to their suppliers who in turn contact their suppliers and so on. A store may have hundreds of food items, each with a list of ingredients. Hundreds or thousands of businesses can be affected, right back to the farm level.

Others pointed out that their parents make decisions about what to buy, since they are the ones going to the grocery store.

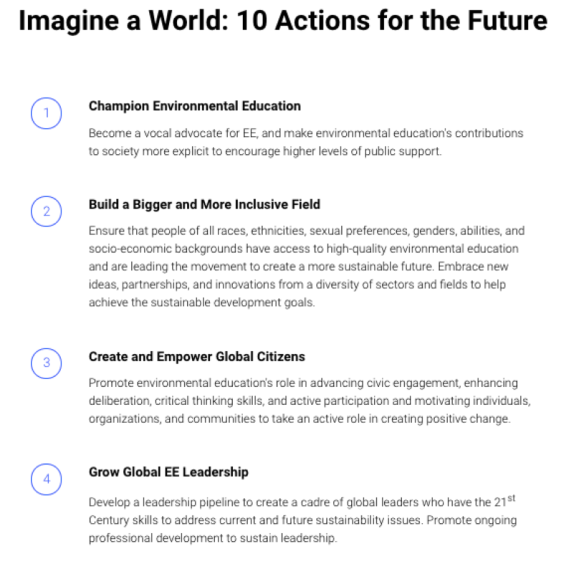

The deconstructing of a happy meal became a transformative learning experience for all those involved, including Mark, the teacher. The happy meal brought out issues, tensions, dissonance, north-south relationships, health issues, ethics, the role of corporations, consumerism, economics, crop-biodiversity, etc. It made an ordinary activity (going to McDonalds), somewhat unordinary and raised many critical questions that demanded some serious reflection. It developed a range of competencies in the students: asking questions, finding reliable information using a variety of sources, analysing data, presenting information, critical thinking, etc., etc.

Mark’s point of it all was not that students would reject going to McDonalds but that they would become aware of range of food-related issues: ethical ones with respect to using GMO-food or not, or with respect to children making toys for children, or which also raises questions about animal-well in relation to industrial agriculture, ecological ones, for instance, with respect to the potential loss of agro-biodiversity, environmental ones, for instance, with respects to the use of batteries in toys, the use of plastics or the energy used in food miles travelled or in ‘producing meat’ , and then there are economic ones, as well, for instance, with respect of the economies of scale of mass-production and consumption but also with respect to the shortening of food-chains and going local, when factoring in so-called “hidden” environmental costs.

Obviously, students can still choose, having considered all aspects and given their own situation, socially and economically and so on, to go to McDonalds but in all likelihood, having done an activity like this will have transformed the way they look at (fast) food. How this episode of transformative learning will affect who they are, who they’d like to become and how they will behave in the future cannot be known or measured shortly after the activity or even months of years later. This will depend on future experiences and circumstances, but what we do know is that having a learning experience like this will make learners a bit more conscious of what they eat and how this may impact themselves and the world around them.

Post-script:

Deconstructing a Happy Meal is a composite example based on a number of stories and ideas from critical teachers engaged with transformative learning and problem-posing-based teaching. The Happy Meal represents many forms of fast food and just as easily could have been built around other meals. The activity is meant to be educational and not prescriptive in that it tells people what to think and how to behave. It should be recognized that McDonalds, like many multi-nationals, are aware of their ecological footprints and have a range of sustainability and environmental-oriented policies and guidelines. Whether these efforts are genuine driven by a deep concern about the well-being of people and planet or driven by purely economic interests is in the eyes of the beholder.

The Happy Meal case has been presented at several international meetings on Education for Sustainable Development. For references to this example and type of learning please go to:

Wals, A.E.J. (2010) Mirroring, Gestaltswitching and Transformative Social Learning: stepping stones for developing sustainability competence. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, (11(4), 380-390.

Sriskandarajah, N, Tidball, K, Wals, A.E.J., Blackmore, C. and Bawden, R. (2010) Resilience in learning systems: case studies in university education. Environmental Education Research, 16(5/6), 559-573.

Sustainability Science Key Issues Edited by Ariane König (Université du Luxembourg, Luxembourg) and Jerome Ravetz (Oxford University, UK) is a comprehensive textbook for undergraduates and postgraduates from any disciplinary background studying the theory and practice of sustainability science. Each chapter takes a critical and reflective stance on a key issue of sustainability from contributors with diverse disciplinary perspectives such as economics, physics, agronomy and ecology. This is the ideal book for students and researchers engaged in problem and project based learning in sustainability science.

Sustainability Science Key Issues Edited by Ariane König (Université du Luxembourg, Luxembourg) and Jerome Ravetz (Oxford University, UK) is a comprehensive textbook for undergraduates and postgraduates from any disciplinary background studying the theory and practice of sustainability science. Each chapter takes a critical and reflective stance on a key issue of sustainability from contributors with diverse disciplinary perspectives such as economics, physics, agronomy and ecology. This is the ideal book for students and researchers engaged in problem and project based learning in sustainability science.